AI-Generated Imagery and Creative Ownership

I know the AI did all the work, but I was surprised to be proud of what it created.

Hello, and please welcome the new subscribers of Photo AI! If you’re not subscribed and reading this on the web, click here to subscribe for a free or paid subscription, either of which help me as an independent journalist and photographer. As a quick reminder, I’m on Mastodon at @jeffcarlson@twit.social, and co-host the podcasts PhotoActive and Photocombobulate.

First Thing

It’s been a busy few weeks of AI-related news. I do think things will level out, but not for a while. AI and machine learning technologies have captured the popular imagination (at least in the media), as much for what it can do as for what people think it might do. Honestly, that’s a nice pocket to be in, because we’re all learning about it in real time.

Emphasis on learning. In the latest episode of the Photocombobulate podcast that I co-host with Mason Marsh, we’re thrilled to talk to Mark Heaps about how to view these tools in their current states, how they can be helpful and harmful to creatives, and just how much electrical and computing resources is required behind the scenes to make these scenes. Mark is a designer, photographer, speaker, and in his day job the Senior VP of Brand and Creative at Groq, a company making processors that take advantage of the unique demands of machine-language computing. It’s one of my favorite episodes we’ve made. Give it a listen (and boost/subscribe/follow if you’re so inclined!): Photocombobulate 29: AI with Mark Heaps.

Here’s the video version:

A Surprising Sense of Creative Ownership

When I was making AI-generated images using Adobe Firefly for last week’s newsletter, I was struck not only by how good some of the results were, but also by a surprising feeling: creative ownership.

Now, that doesn’t make much sense.

On the surface, Generative AI involves very little creative “work.” You type a phrase describing what you’d like to see, and after a few seconds or minutes, the service generates a set of possibilities that attempt to match the description. It doesn’t matter if I’m a good photographer, or great at Photoshop, or see light in a different way than people who aren’t photographers or artists. The result is, by many empirical standards, of better quality than I could make without the software’s assistance, particularly given the minimal effort put into it.

And yet.

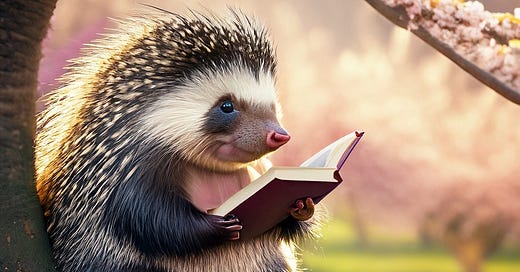

I typed “porcupine reading a book at the base of a tree blooming cherry blossoms in spring” which resulted in an image that I immediately fell in love with. It made me want to know more about why this particular porcupine is hanging out there and what he’s reading. It immediately invoked a story I wanted to follow.

I also created a striking portrait of a woman by typing “young black bald woman in a black tank top portrait bokeh at night in front of a neon sign _photo”. (The underscore denotes one of the options Firefly presents, in this case specifying a “photo” image instead of an “art” image; when you save the image to disk, the filename includes the entire text prompt.) I really like how the image turned out—weird disconnected earring notwithstanding—and think about what it would take to shoot this portrait in the real world, with its challenges of setting up lighting and location and coordinating with a model.

When the result appeared, I felt a similar sensation as when I run across an image in my library where all the elements come together to make a good photo. I got that “good job Jeff” sensation that is often fleeting for photographers (even the ones not named Jeff).

Is having a sense of creative accomplishment even fair when talking about GenAI? Did I really create those images? It’s a murky question. The US Copyright Office has weighed in a few times so far. In February 2023, it denied copyright to Midjourney-created images in a graphic novel, but affirmed copyright for the text. In March 2023, the office elaborated its stance and called for additional public guidance. It also indicated the importance of human-created artworks (emphasis mine):

In the Office's view, it is well-established that copyright can protect only material that is the product of human creativity. Most fundamentally, the term “author,” which is used in both the Constitution and the Copyright Act, excludes non-humans. The Office's registration policies and regulations reflect statutory and judicial guidance on this issue.

This is a legal interpretation, which I feel runs alongside the bigger question: why did I feel as if I had created those works?

I think some of it is appreciation that Firefly made aesthetically pleasing results. For instance, I get the same feeling when I view other people’s photos I like in the Glass app. I appreciate the finished product.

But there’s also the ephemeral nature of these AI-generated works. If you go back to the previous newsletter, you’ll see that the image of the porcupine reading a book is different from the images above, even though both were made using the exact same text prompt.

This is considered an annoyance now, because people may want to generate different scenes using the same characters or elements. (In Firefly you can in a limited way: click the three-dot icon and choose Use as Reference Image. The ability to upload your own source images is not yet implemented.)

That limitation, though, gives AI art something sought after by art collectors and patrons for centuries: uniqueness. Just as the distinctive brush strokes of a Monet painting make it singularly unique—even if it’s one of a series of paintings of the same scene, or even copies of other versions—every output from a GenAI service is different from every other.

Plus, regardless of the mechanism of their creation, and despite the fact that the mechanism was created using machine learning models built on millions of existing images, none of my images existed at all until I summoned them into being.

And yes, I did just say “my” images.

Further AI/ML Reading

We’ve discovered the best phrase to describe the problem of biased source data, courtesy of Melissa Heikkilä at Technology Review’s The Algorithm: “Pale, male, and stale.”

Although I’ve written a lot about how our biases are reflected in AI models, it still felt jarring to see exactly how pale, male, and stale the humans of AI are. That was particularly true for DALL-E 2, which generates white men 97% of the time when given prompts like “CEO” or “director.”

In one of the last articles to appear in DPReview, Dale Baskin writes about the state of the camera industry. The section, “We’re just getting started with AI,” really stuck out to me. While Apple and Google have advanced the state of the art for AI-assisted photo processing, the traditional camera manufacturers have seemed glacial in their response.

If there’s another thing every camera company can agree on, it’s that they want the letters ‘AI’ on their products. Today, AI is used chiefly to deliver improved subject recognition and tracking using algorithms trained by machine learning. AI will get more sophisticated, probably quickly, and a few insiders shared off-the-record examples of what we might see.

Imagine a camera that analyzes what’s in the viewfinder and understands that you’re shooting a sporting event. The camera might evaluate the first few frames in a burst shot to determine if there’s motion blur and, if necessary, increase the shutter speed in real-time to compensate. It might also adjust your burst rate on the fly based on how much the image changes between frames.Speaking of AI in cameras, we’re starting to see a next evolution of in-camera recognition technology. Being able to identify a face and use that to track focus is one thing. Now the Canon R3 can identify individual people. If you’re on vacation where there are a lot of other people, and a family member is among them, the camera would be able to say, “Hey, there’s Irene!” and lock focus. (I’m sure my PhotoActive podcast co-host Kirk McElhearn is saying, “Yes, but when will it be able to do the same for my cats?”) Read more in The Canon R3 Can Now Remember Specific Faces and Focus On Them.

Let’s Connect

Thanks again for reading and recommending Photo AI to others who would be interested. Send any questions, tips, or suggestions for what you’d like to see covered at jeff@jeffcarlson.com. Are these emails too long? Too short? Let me know.

Excellently put. I was really aiming to understand the internal conflict I was feeling, knowing that my involvement in the creation was minimal, and yet being able to say, “Look what I did!” Thanks for your comment, Johan.

That illusion of accomplishment is a core psychological trap of gen-AI, and "text-to-image" is a dangerously misleading term in that reinforces that perverse allure.

They position it as if you, out of your creative genius, expressed through your masterfully crafted prompt, birthed an original image out of mere noise.

When all you did was to find a pretty stick in latent space. One random point inbetween a statistical average of all other pictures; one that a billion other people could have also found, and would be identical from the same prompt if not for the tiny bit of randomness added by the service.

That image was built on somebody else's creative choices, sense of aesthetics, craft and effort. You can give some direction, but can't add sufficient control to claim ownership.

Prompting is searching. Which makes claiming creative ownership and copyright over the output is ridiculous.

But the allure is so, so strong.